On December 7, 1941 Yiayia and Papou stood in their New Kensington, PA kitchen - stunned as they listened to their RCA Victor radio. The Japanese had attacked Pear Harbor. And they agonized - how could such a thing happen in this great land of promise? Finally, the sleeping giant they'd come to love would enter World War II. And so Yiayia and Papou looked to a man they revered for guidance and comfort: President Franklin D. Roosevelt. In his Fireside Chat on December 9, he urged the nation to prepare to make sacrifices.

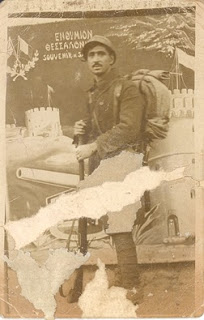

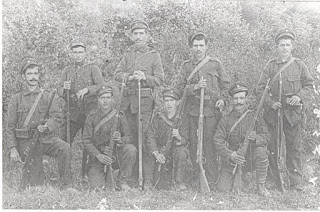

Yiayia and Papou were eager to meet that directive for three reasons: 1) Their countrymen in Greece were suffering unspeakable atrocities under Axis occupation. And the fate of the beloved mother and siblings Yiayia had left behind was still achingly uncertain. 2) As the below pictures illustrate, Papou fought in WWI on the northern borders of Greece. Wounded by enemy gunfire, he would never forget the mammoth vitriol of the formidable Axis. 3) Patriotism - Yiayia and Papou were incredibly proud to be Greek Americans and would do anything for the country they'd come to love.

So as the American economy converted to war production, they hunkered down. Too old to join the military, Papou worked at "The Busy Bee" now open 24/7. "Rosie the Riveter" became a symbol of patriotic womanhood that deeply resonated in their bustling industrial town. Many of Yiayia's new friends went to work at the mainstay of the New Kensington economy: The Alcoa aluminum plant. Yiayia still tended home and hearth, but like her neighbors, she created a "Victory Garden" to help alleviate food shortages.

As the country faced intense price controls and rationing, she taught daughters Chrysanthy and Anastasia to recycle everything: rags, paper, string, and metal scrap for the US military effort. One day, my father saw Yiayia peel the label off a metal can, then flatten it with her foot. "Why are you doing that, Mama?" he asked. She simply replied, "So they can make battleships, Tasso." And he marveled--how in the world can a battleship be made out of cans? Well, Yiayia was about to teach him even more about wartime sacrifice.

Over the next four years she would send little Tasso in his Junior Commando uniform - badge, stripes and all - out into the neighborhood. Ever the disciplinarian, she'd caution--"Mi mas manis rezili" (do not shame the family name). And so pulling his red wagon, Tasso ventured door to door to collect newspapers and cans of lard (later used to produce explosives); Yiayia then deposited them in the nearby recycling center. And such was the norm until one day Tasso witnessed something haunting.

At the nearby railroad station, large wooden crates were being unloaded. He later asked, "What were they, Mama?" And so, like many American mothers, Yiayia would explain a painful new reality. In her native Greek language she said, "Some soldiers are coming home, Tasso. They didn't make it. Many of them were our neighbors." As Yiayia had learned from her mother and would now pass on to her son ~ "such is the life" ~ and thus Americans had no choice but to adapt and to endure. Yes, Yiayia and the countrymen she'd come to love would grieve together again and again. But soon a loss would come ~ one that would be more symbolic and momentous than anyone could imagine.